Ever sat in a meeting, drowning in data, wondering how to make sense of it all?

You’re not alone.

Most professionals were never taught how to structure their thinking. We’re handed complex problems and expected to figure them out. Meanwhile, consultants from firms like McKinsey, BCG, and Bain walk into the same chaos and somehow cut through it in a matter of hours.

Here’s the thing: they don’t have secret knowledge. They have thinking systems. And those systems aren’t locked behind an MBA or a consulting career. Anyone can learn them.

In this blog, I’ll walk you through:

- Why consulting frameworks matter for non-consultants

- The core thinking principles behind every consulting tool

- How to apply these tools in your everyday work, starting this week

Let’s start with why this matters more than you might think.

Why Consulting Frameworks Aren’t Just for Consultants?

A McKinsey survey of 15,000 people found that over 50% of employees report being “relatively unproductive” at work. That’s not because they’re lazy. It’s because they’re overwhelmed.

Here’s another stat that should bother you: employees spend 60% of their time on “work about work.” That means organizing information, sitting in meetings, and chasing updates instead of actually solving problems.

The missing skill?

Structured thinking.

Most professionals immediately jump into research mode when faced with a challenge. They gather data, read reports, and attend meetings, hoping clarity will emerge. It rarely does.

What Consultants Actually Do Differently?

I once worked with a marketing manager named Sarah who was stuck on a customer retention problem. She’d been analyzing data for three weeks. Spreadsheets everywhere. No clear direction.

When I asked her what she thought was causing the problem, she said, “I don’t know yet. I’m still looking at the data.”

That’s the trap.

Consultants don’t start with data. They start with a hypothesis. They structure the problem before conducting their research. They know what they’re looking for before they open a spreadsheet.

The difference isn’t WHAT they know.

It’s HOW they think.

And that’s a skill you can build. If you want to go deeper on this, the structured problem-solving guide breaks this down in detail.

The Core Thinking Principles Behind Every Consulting Tool

Before learning any specific tool, you need to understand the principles that make it work. These aren’t secrets. They’re habits anyone can build.

1. Break Big Problems Into Smaller Pieces

Complex problems feel overwhelming because we try to solve them all at once.

Consultants do the opposite. They break big problems into smaller, manageable pieces. Each piece can be analyzed independently, and the sum of those analyses creates the full picture.

- Before: “We need to improve profitability.”

- After: “Profitability has two levers: revenue and costs. Revenue depends on price and volume. Costs break down into fixed and variable. Let’s analyze each.”

See the difference?

The second version gives you a roadmap.

2. Start With a Hypothesis, Not a Blank Page

Most people start research with an open mind.

“Let’s see what the data tells us.”

That sounds smart. It’s actually inefficient.

Consultants start with a hypothesis, an educated guess about what’s causing the problem or what the solution might be. Then they test it. If the data supports it, they refine it. If not, they pivot. This approach cuts research time dramatically. Instead of exploring everything, you’re testing something specific.

Instead of “Let’s figure out why this project is delayed,” try “I believe the project is delayed because of unclear requirements in Phase 2. Let me validate that.”

3. Organize Your Thinking So Others Can Follow

You might have brilliant ideas.

But if you can’t communicate them clearly, they don’t matter.

Consultants structure their communication so the audience can follow the logic. They lead with the answer, then provide supporting evidence. They use clear categories. They anticipate questions.

This is what’s often called top-down communication, and it transforms how people receive your ideas.

4. Separate “What You Know” From “What You Assume”

Every analysis contains facts and assumptions.

The problem? Most people mix them together.

Consultants explicitly separate what they know (data and evidence) from what they assume (interpretations and beliefs). This clarity helps identify where more research is needed and where conclusions are solid.

Here’s what this looks like in practice:

| What You Know (Facts) | What You Assume (Beliefs) |

| Sales dropped 15% last quarter | Customers are leaving because of the price |

| Three competitors launched similar products | Our product is becoming commoditized |

| Customer complaints increased by 40% | Our support team is underperforming |

Notice how the “assumptions” column contains interpretations that FEEL like facts but haven’t been validated. Strong thinkers constantly ask: “Is this something I know, or something I believe?”

| 🎯 TRY THIS EXERCISE |

| Next time you face a problem at work, write down your hypothesis BEFORE you start researching. Just one sentence: “I believe the problem is caused by X” or “I think the best solution is Y.” Notice how it sharpens your focus. Instead of wandering through data, you’re testing a specific idea. |

If you’re serious about building consulting skills systematically, the High Bridge Academy Business Excellence Bootcamp offers immersive training led by ex-McKinsey, BCG, and Bain consultants. It’s designed specifically for professionals who want the toolkit without the consulting career.

5 Core Consulting Thinking Tools (And How to Use Each)

Now let’s get practical.

Below are five thinking tools that consultants rely on daily. I’m not going to give you the academic definitions. I’m going to show you how to actually use them.

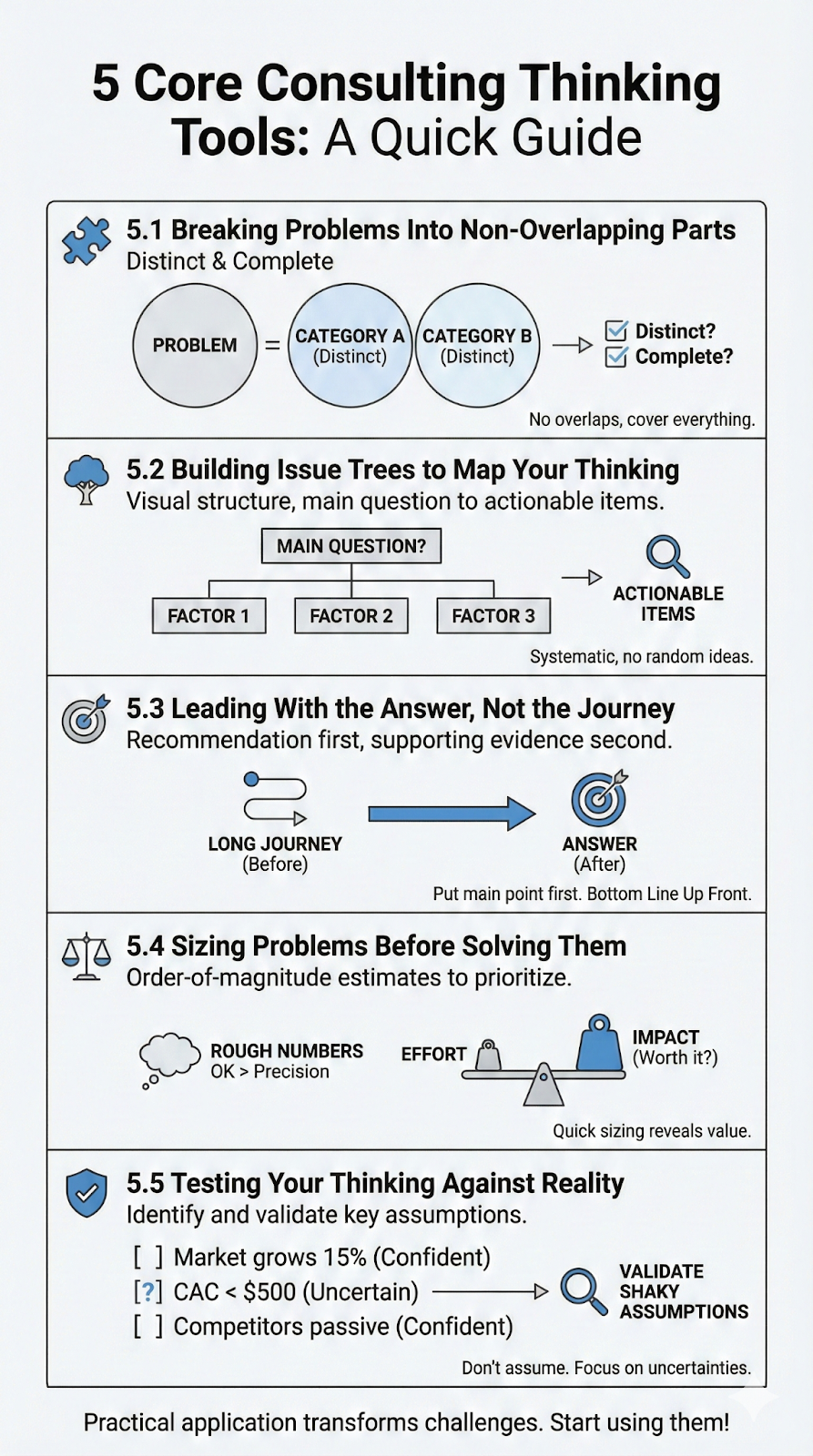

Tool #1: Breaking Problems Into Non-Overlapping Parts

When you divide a problem into categories, those categories should be distinct (no overlap) and complete (nothing missing). This ensures your analysis covers everything without redundancy. This principle is foundational.

Get it wrong, and your entire analysis falls apart. Get it right, and complex problems suddenly become manageable.

- Before: A sales team analyzing declining revenue looks at “marketing issues,” “sales issues,” and “customer issues.” But wait, aren’t customer issues related to both marketing and sales? The categories overlap, creating confusion, and team members argue about where specific problems belong. Time gets wasted on categorization debates instead of solving problems.

- After: The same team restructures their analysis: “Revenue = Price × Volume. Price is stable. Volume is down. Volume depends on new customers and retention. New customer acquisition is down 15%. Retention is flat.” Now each category is distinct, and they’ve identified exactly where to focus. No debates about categorization. Just clear direction.

How to apply it: When breaking down any problem, ask two questions:

- Are these categories distinct? (No overlap)

- Do they cover everything? (Nothing missing)

If you can answer yes to both, you have a solid structure. If not, keep refining until you do.

Tool #2: Building Issue Trees to Map Your Thinking

An issue tree is a visual structure that shows all the factors influencing an outcome. It starts with your main question and branches into sub-questions until you reach actionable items.

- Before: A team investigating project delays discusses causes randomly: “Maybe it’s the vendor.” “Could be the budget.” “What about the timeline?” Ideas fly around with no structure.

- After: They build an issue tree. The main question: “Why is the project delayed?” branches into three categories: People, Process, and External Factors. Each category branches further. “People” breaks into team capacity, skill gaps, and turnover. Now they can systematically investigate each branch.

How to apply it: Start with your main question at the top. Ask “What are the 3-4 major factors that could explain this?” For each factor, ask the same question again. Keep branching until you reach specific, testable items.

For more on this approach, check out the guide on defining problems effectively.

Tool #3: Leading With the Answer, Not the Journey

Most people communicate chronologically: “First I did this, then I found that, which led me to conclude X.”

Consultants flip it: “My recommendation is X. Here’s the supporting evidence.”

- Before (email to your manager): “Hi, I’ve been analyzing the Q3 data. I looked at customer segments, regional performance, and product categories. After comparing trends and reviewing historical patterns, I noticed something interesting in the enterprise segment…” Your manager stops reading.

- After (same information, restructured): “Recommendation: Focus Q4 marketing budget on the enterprise segment. It’s growing 23% while other segments are flat. Supporting data below.” Your manager immediately understands your point and can decide whether to read more.

How to apply it: Before sending any communication, ask: “What’s my main point?” Put that first. Everything else is supporting evidence. This connects directly to presentation storytelling techniques that transform how audiences receive your ideas.

Tool #4: Sizing Problems Before Solving Them

Before investing time in a solution, estimate whether it’s worth pursuing. Quick, rough calculations can prevent weeks of wasted effort.

- Before: A product team spends six weeks building a feature that, when launched, impacts only 2% of users. Nobody asked whether this was the best use of time.

- After: The same team estimates upfront: “This feature affects our enterprise tier. That’s 500 of our 10,000 customers. Even if it increases their retention by 10%, that’s 50 customers. At a value of $5,000 annually each, we’re talking about a $ 250,000 impact. Is six weeks of engineering time worth $250K? Yes. Proceed.”

How to apply it: Use order-of-magnitude thinking. You don’t need precision. You need to know if something is worth 10 hours or 100 hours of effort. Rough numbers are fine.

Tool #5: Testing Your Thinking Against Reality

Before finalizing a recommendation, identify what must be true for it to work. Then ask: “Am I confident these things are actually true?”

- Before: A team recommends entering a new market based on its growth rate. They don’t question whether they can actually compete there.

- After: The same team lists key assumptions:

- The market will continue growing at 15% annually

- Our product meets the needs of customers in this market

- We can acquire customers at a cost below $500 each

- Competitors won’t respond aggressively

Now they can evaluate each assumption. If assumption #3 is shaky, they need to validate it before proceeding.

How to apply it: After forming a recommendation, ask: “What must be true for this to work?” List 3-5 key assumptions. Rank them by how confident you are. Focus your validation on the least certain ones.

Real-World Applications of Consulting Frameworks: When to Use What?

Knowing these tools is one thing. Knowing WHEN to use them is another. Here’s a quick reference guide based on the type of challenge you’re facing.

| Your Challenge | Thinking Tool to Use | Example Application |

| “I have too much data and don’t know where to start.” | Breaking into non-overlapping parts | Organize customer feedback into distinct categories: product, service, pricing, and delivery |

| “My recommendation keeps getting pushback.” | Leading with the answer | Restructure your next email to state your conclusion first |

| “I’m not sure if this project is worth pursuing.” | Sizing problems first | Estimate potential impact before committing resources |

| “Our team keeps going in circles on this decision.” | Building an issue tree | Map all decision factors visually so nothing is missed |

| “I made a recommendation, but I’m not confident.” | Testing against reality | List and validate your key assumptions |

| “I need to explain something complex to leadership.” | Leading with the answer + non-overlapping parts | Structure your message with a clear recommendation and 3 distinct supporting points |

Combining Tools for Complex Situations

Most real-world problems require multiple tools working together. Here’s how that looks in practice:

Let’s take a scenario: Your company is deciding whether to expand into a new market.

- Step 1 (Sizing): Estimate the market opportunity. Is it worth $1M or $100M? This determines how much effort to invest in analysis.

- Step 2 (Issue Tree): Map out all the factors that would determine success: market attractiveness, competitive dynamics, internal capabilities, and financial requirements.

- Step 3 (Non-Overlapping Parts): Ensure your categories don’t overlap. “Competitive dynamics” and “market attractiveness” might overlap if not carefully defined.

- Step 4 (Testing Assumptions): Identify what must be true. “We assume we can acquire customers for under $200 each. We assume the regulatory environment won’t change. We assume our product meets local requirements.”

- Step 5 (Leading With the Answer): Present your recommendation first. “We should enter this market, but only if we can validate our customer acquisition cost assumption within 90 days.”

The goal isn’t to memorize which tool goes with which situation. It’s to build the habit of asking, “What’s the best way to structure my thinking here?”

That question alone puts you ahead of most professionals.

If you’re managing a team and want to build these skills across your organization, it’s worth looking at how best onboarding examples from high-growth companies integrate structured thinking from day one.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Using Consulting Frameworks

I’ve seen professionals get excited about these tools, try them once, and give up. Here’s why that happens, and how to avoid the same traps.

- Trying to apply everything at once. Start with ONE tool. Master it. Then add another. Trying to overhaul your entire thinking process in a week leads to frustration, not improvement. Pick the tool that addresses your biggest current pain point.

- Using the tool as a substitute for thinking. These are guides, not answers. If you fill in a structure without actually thinking through it, you’ll get structured nonsense. The structure should help you think more clearly, not replace the thinking altogether.

- Skipping the “so what” step. The point isn’t to organize information beautifully. It’s to reach a helpful conclusion. Every analysis should answer: “What does this mean? What should we do?” If your beautifully structured document doesn’t lead to a recommendation, it’s just decoration.

- Not adapting to your audience. A detailed issue tree might impress your manager, but it may confuse your colleague in another department. Match your communication style to who you’re talking to. Sometimes, a simple email is more effective than a complex diagram.

| ⚠️ Warning |

| If you find yourself saying “but the framework says…” to justify a recommendation, you’ve missed the point. These tools are meant to serve your thinking, not replace it. The moment you’re defending a structure instead of defending your logic, step back and reconsider. |

For more on handling disagreements when your structured analysis conflicts with popular opinion, check out how to disagree courageously.

How to Start Building These Consulting Skills This Week?

You don’t need an MBA to start thinking like a consultant. You just need to be intentional. Here’s a simple 5-step plan you can start today.

Step 1: Pick One Problem You’re Currently Facing

Choose something real, not hypothetical. It should be something you’ll work on this week. Maybe it’s a decision you need to make, a presentation you’re preparing, or a project that’s stuck. The key is relevance. Learning by doing beats learning by reading every time.

Step 2: Write Down Your Hypothesis Before You Research

Force yourself to commit to a direction before you gather more data. Write one sentence: “I believe [the problem] is caused by [X]” or “I think the best solution is [Y].” This feels uncomfortable at first. That’s normal. The discomfort is the learning happening.

Step 3: Break the Problem Into 3-5 Non-Overlapping Parts

Draw it out on paper, a whiteboard, or a simple document. Start with your main question and identify 3-5 categories that could explain or address it.

Ask yourself:

- Are these categories distinct? (No overlap)

- Do they cover everything relevant? (Nothing missing)

If not, revise until they do.

Step 4: Identify Your Top 3 Assumptions

What must be true for your hypothesis to hold? Write down three things you’re assuming but haven’t verified. Then rank them: Which assumption are you least confident about? That’s where you should focus your validation effort.

Step 5: Present Your Thinking to Someone Else

Find a colleague, a friend, or even just talk out loud to yourself. Explain your structure before sharing your conclusion. Notice where they get confused. That’s where your thinking needs work. Their questions reveal the gaps in your logic.

| 🎮 Fun Activity: The Newspaper Test |

| Here’s a quick exercise you can do right now:Pick up any business article or internal reportFind a recommendation or conclusion in itAsk: “What are the 3 key assumptions behind this?”Ask: “How would I validate each one?”Do this with 5 articles this week. You’ll start noticing assumptions everywhere, and your ability to spot weak logic will dramatically improve.Bonus: Try it on your own past work. You’ll be surprised how many unvalidated assumptions you find. |

If you want to level up faster, consider exploring how companies use soft skills training to develop these capabilities at scale.

What Separates Good Practitioners From Great Ones?

Good practitioners know the tools.

Great practitioners know when NOT to use them.

I once worked with an operations director named Maria who was so excited about structured thinking that she tried to force-fit every conversation into a framework. Team meetings became exercises in categorization. Casual brainstorms turned into issue tree workshops.

Her team started avoiding her.

The lesson? Structure serves communication, not the other way around. Sometimes, the best response to a colleague’s question is a simple answer, rather than a structured analysis.

The Three Levels of Mastery

- Level 1: Tool User – You know the tools and can apply them when prompted. You follow the steps mechanically. This is where everyone starts.

- Level 2: Adaptive Practitioner – You recognize which situations call for which tools. You modify and combine approaches based on context. You know when structure helps and when it gets in the way.

- Level 3: Invisible Expert – You think structurally without conscious effort. Your communication is naturally clear. Others can’t see the “framework” because it’s seamlessly integrated into how you work.

Most professionals get stuck at Level 1. They learn the tools but never develop the judgment to apply them appropriately. The jump to Level 2 requires deliberate practice and feedback. The jump to Level 3 requires years of experience and continuous refinement.

Great practitioners also recognize that these skills compound over time. Every problem you solve well builds your reputation. Every clear recommendation earns trust. Every structured presentation makes the next one easier to deliver.

But the real differentiator?

Great practitioners teach others. They don’t hoard these skills. They share them with their teams, their peers, and their organizations. That’s how these capabilities scale beyond one person.

How to Know If You’re Making Progress?

Unlike technical skills, structured thinking is hard to measure. You can’t take a certification exam. There’s no obvious credential to earn.

But there are clear signals that your thinking is improving. Here are the signs to look for:

- Your recommendations get less pushback: When your thinking is clear, people can follow your logic even if they disagree with your conclusion. You spend less time defending your process and more time discussing the substance. Meetings become shorter because there’s less back-and-forth clarifying what you mean.

- You waste less time in research mode: Instead of gathering data endlessly, you know what you’re looking for and why. You can recognize when you have enough information to move forward. You stop saying “I need more data” and start saying “Based on what we know, here’s what I recommend.”

- People start asking for your input more often: Structured thinkers become go-to people for challenging problems. Colleagues notice when someone can cut through complexity and reach clarity quickly. If you’re getting pulled into more cross-functional discussions, it’s a sign your thinking is valued.

- You can explain complex ideas in simple terms: Clarity is the ultimate test of understanding. If you can’t simplify it, you haven’t structured it well enough. When you find yourself explaining things more clearly, you know your thinking has improved.

- You catch yourself thinking structurally without trying: This is the ultimate sign of progress. When you automatically break problems into pieces, form hypotheses before conducting research, and lead with answers, the skills have become habits.

If you find yourself spending MORE time on analysis and LESS time on action, you might be over-applying these tools. Structure should accelerate decisions, not delay them. If your colleagues are saying “Let’s just make a call” while you’re still building issue trees, it’s time to recalibrate.

For more on building collaborative relationships as you develop these skills, check out how to ask for help at work correctly.

Start Thinking Like a Consultant Today!

Consulting frameworks aren’t magic. They’re structured thinking habits that anyone can learn.

The key is practice, not perfection. Start with one tool. Apply it to one real problem. Notice what works and what doesn’t. Build from there. You don’t need a fancy degree or a consulting background to think this way. You need intentional practice and a willingness to structure your thinking before you act. That’s it.

Want to accelerate your growth?

The Business Excellence Bootcamp by High Bridge Academy has trained 1,000+ professionals from companies like McKinsey, BCG, Bain, and Deloitte. Check the upcoming cohort dates if you’re serious about building these capabilities fast. Our faculty of 60+ ex-MBB consultants has helped professionals across industries sharpen their thinking and accelerate their careers.

The ball is in your court.

Start small, think structured and get better.